I was recently a guest on the Forward Guidance podcast, which you can also listen to for my recent detailed views.

In this note, I will make the case for why interest rates need to remain higher for longer based on two arguments.

The first case is based on demographic analysis and the structural changes going on in the economy. To provide some background, I was very early in the last cycle in recognizing that in the post GFC economy, there were many deflationary impulses. The most obvious ones were the deleveraging forces due to the subprime housing collapse, but bank regulations also played a role. More importantly, we had a major demographic overhang the entire cycle.

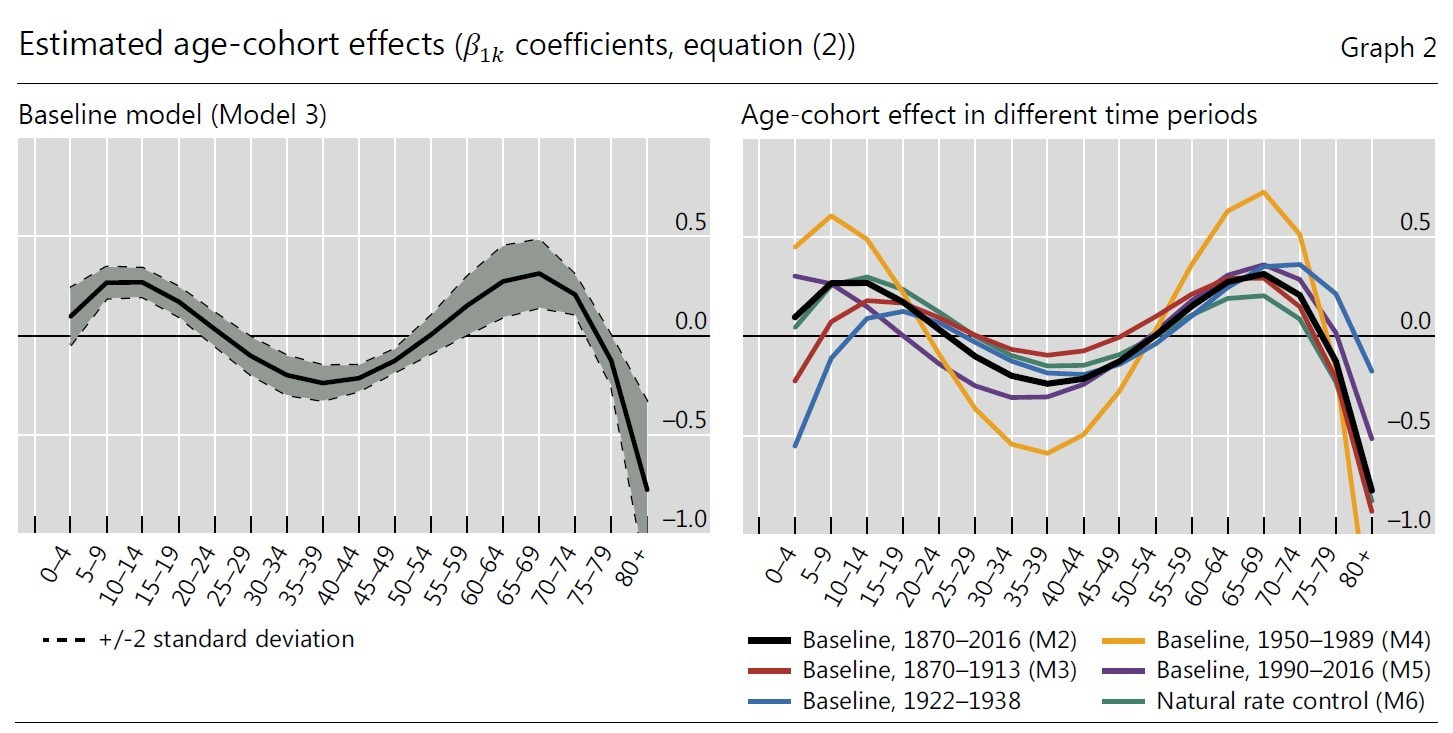

Demographics will not tell you anything that will help you predict this year’s GDP. For that reason, many people ignore it altogether because they feel they cannot design trading strategies around it. In fact, the real value in demographic analysis is in understanding the economy’s capacity and constraints. We do this through studying what is called the life cycle hypothesis. Essentially, as a person progresses through different age groups, their savings, consumption, investment patterns change in predictable ways. Income, wealth accumulation and productivity trends also materialize in predictable ways. Thus, by understanding the changing composition of the labor force, we can then deduce structural changes in the economy. The post GFC period was one dominated by two demographic trends: a surplus of labor from China, which depressed wages throughout the developed world, and the aging of the baby boomer generation as they worked in their final 10 years to retirement. The baby boomer generation was the largest and wealthiest group in the history of the U.S., so their period approaching retirement consisted of elevated savings rates in order to maximize their nest eggs. Both of those forces were large deflationary impulses that happened to coincide with the disinflationary deleveraging dynamics.

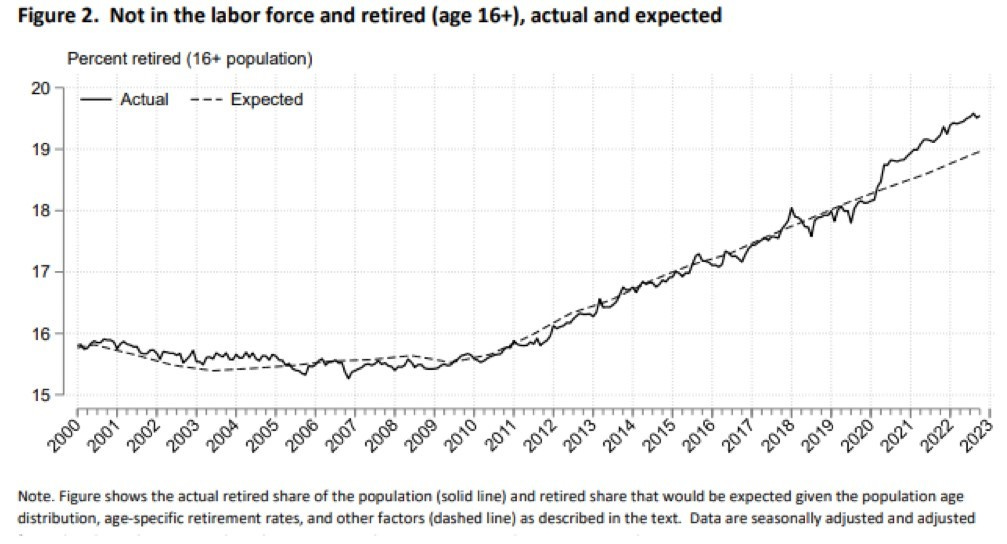

This decade is entirely different. The baby boomers have retired and done so much faster than demographic analysis would have implied. This has reduced labor supply and raised wages. We also dropped the least productive labor force group from the workforce (as people in their 60s don’t work 18 hours/day, they are senior and rest on their established reputations).

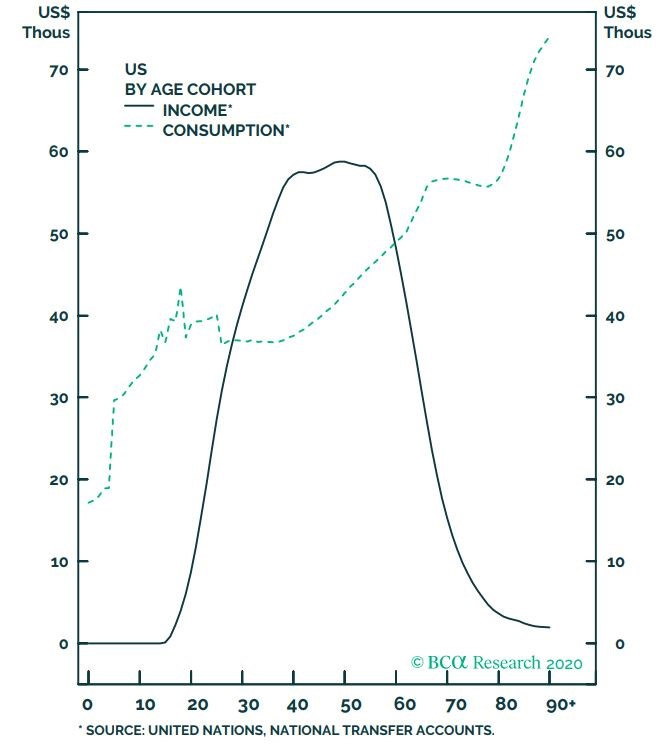

A common misconception is that consumption falls off a cliff in retirement. It does not. In fact, it remains very strong, but what does change is this group goes from becoming a saver (i.e. strong demand for fixed income), to a dissaver (spending down savings). This is inflationary.

The next largest labor force group, millennials, have entered into peak family formation phase. This means transitioning from living in city centres and with a consumption basket on services, i.e. experiences, and moving to consumption of housing, durable goods and things for their families. This is inflationary. Also coincidentally, they are hitting their peak productivity point, which occurs in your early 40s.

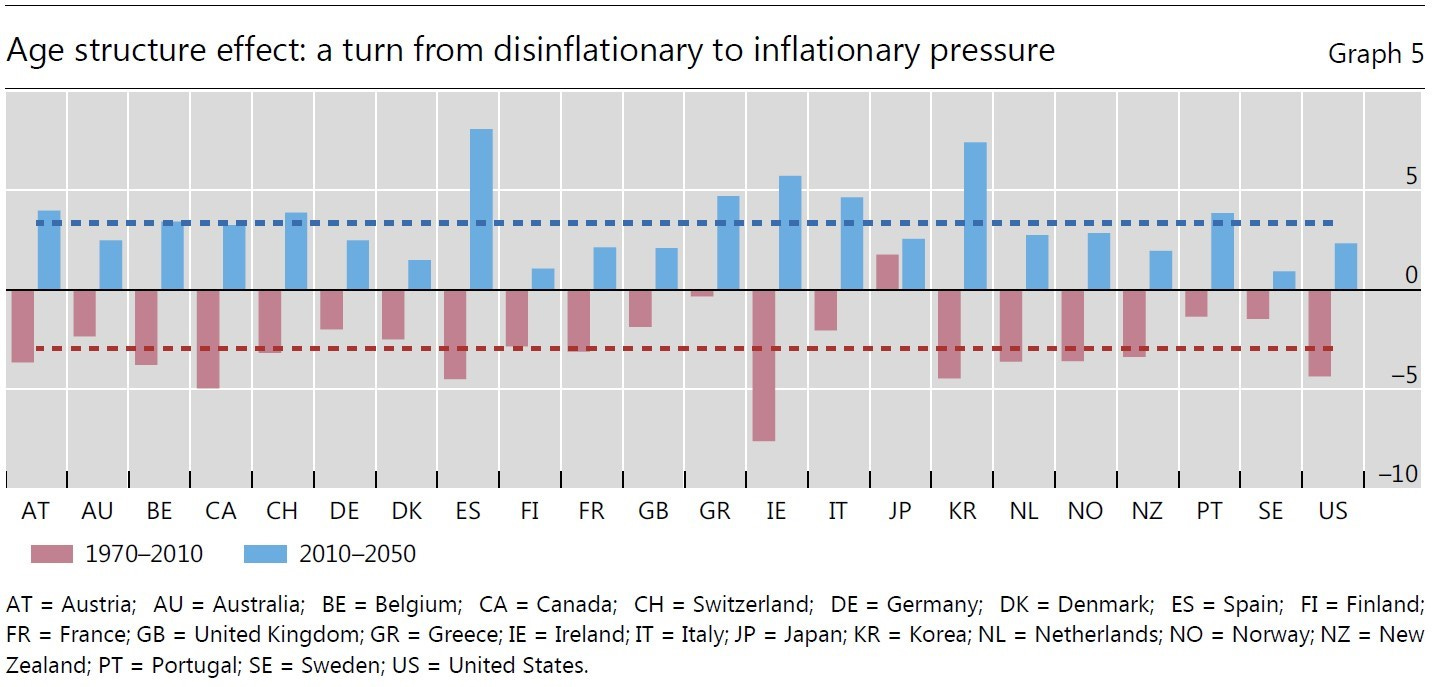

The impulses to inflation by age group are below. The most inflationary groups are called the dependent groups (children and elderly) as they do not save nor produce, yet consume a substantial amount.

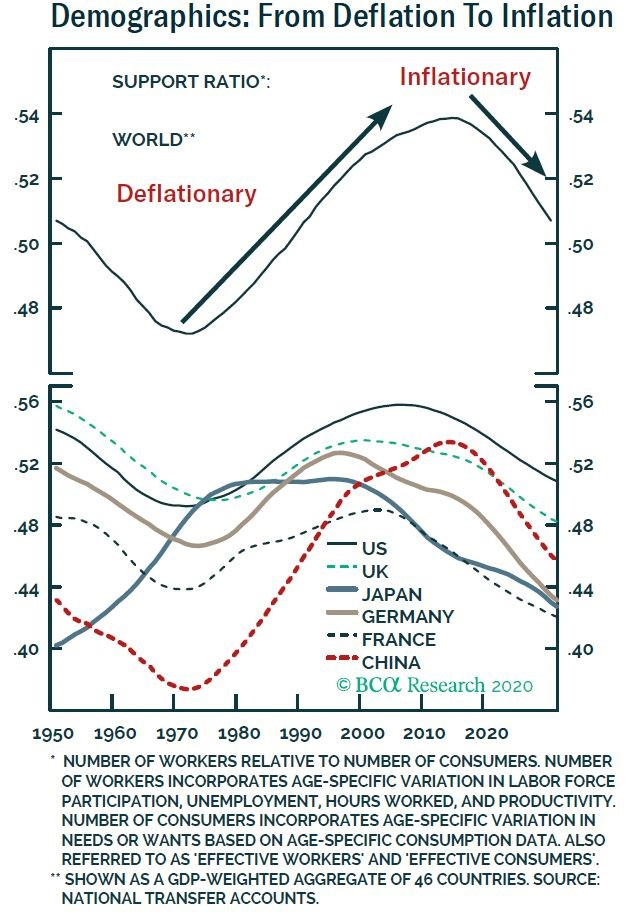

The global support ratio is declining rapidly. In other words, we have fewer workers available to support the dependent groups. This is inflationary.

The impulse from all these changes is shown below.

None of this means we have to have a specific inflation number any given year. Remember, demographics simply tell you the capacity and constraints of the economy, and it is up to us to look at cyclical dynamics as we navigate these trends. However, what the above does tell you is a major force that has a negative beta to inflation now has a positive beta. A headwind has now become a tailwind. These impulses will be with us for a decade or so.

In aggregate, demographics tell us we: reduced the savings rate, increased productivity, increased demand for housing and durable goods in a sticky manner, and have labor shortages and thus higher wages.

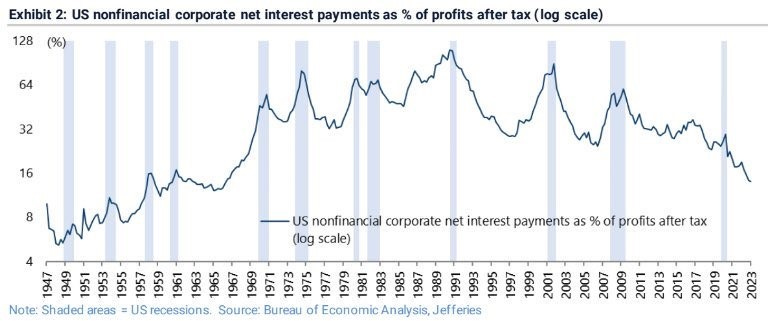

Onto cyclical dynamics. Due to the deleveraging post GFC, both households and corporates entered the COVID episode in good shape. With the extraordinary policy responses in 2020, they were able to improve on that situation by terming out debt. As such, it has been hard to argue that rates are biting either of these groups.

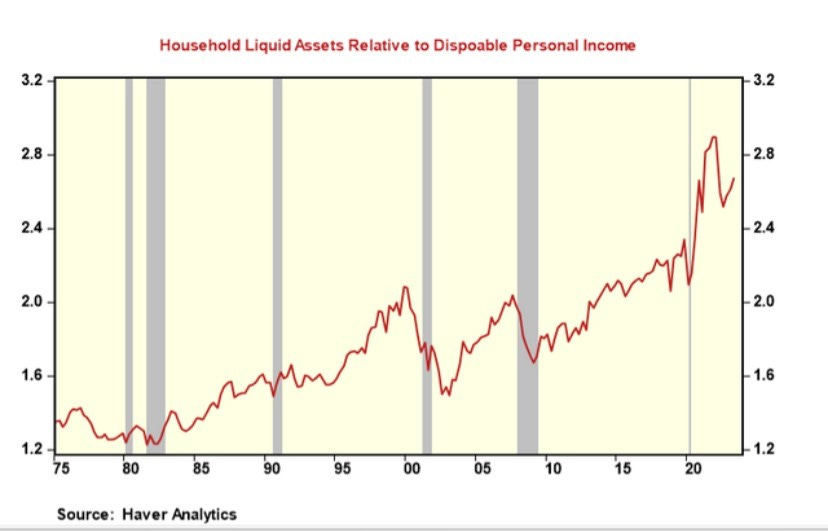

The U.S. household is the cleanest of all countries by far.

With massive liquid assets, which currently earn 5+% for doing nothing.

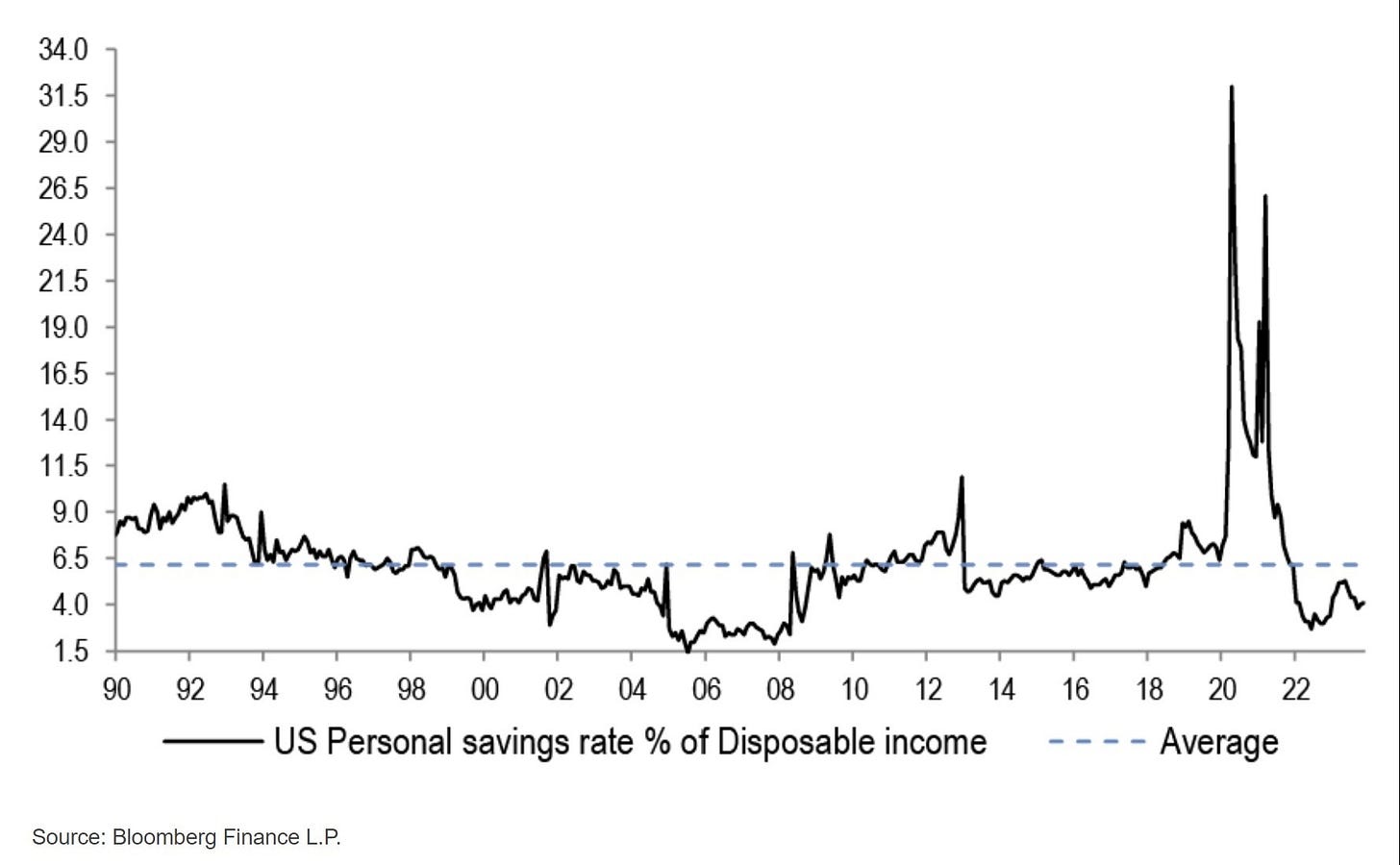

And one of the lowest savings rates in history. Despite these higher rates, consumers are not foregoing consumption to save. They do not see a slowdown in sight.

It’s hard to argue higher rates have hurt the corporate sector either.

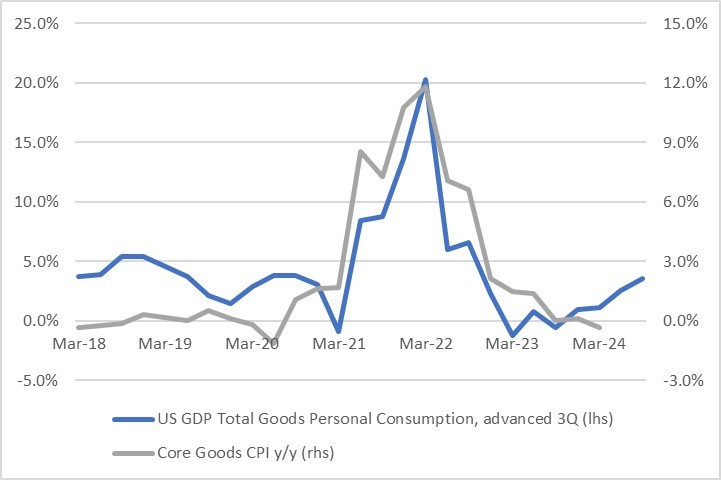

My view is that the economy is in a good place, we have inflation under control, albeit around 3% or so levels, and we have strong growth. Roughly 3% inflation +3-3.5% real GDP = 6-6.5% nominal GDP. This is a very strong economy. Inflation has come down in spite of this strong growth, which was certainly a surprise to me. A big factor was that we had supply side improvements (strong labor force supply, productivity and non residential construction). This has led to goods deflation while we have maintained sticky services inflation. I think too many people are extrapolating these trends into the future.

It looks like core goods inflation has upside from here.

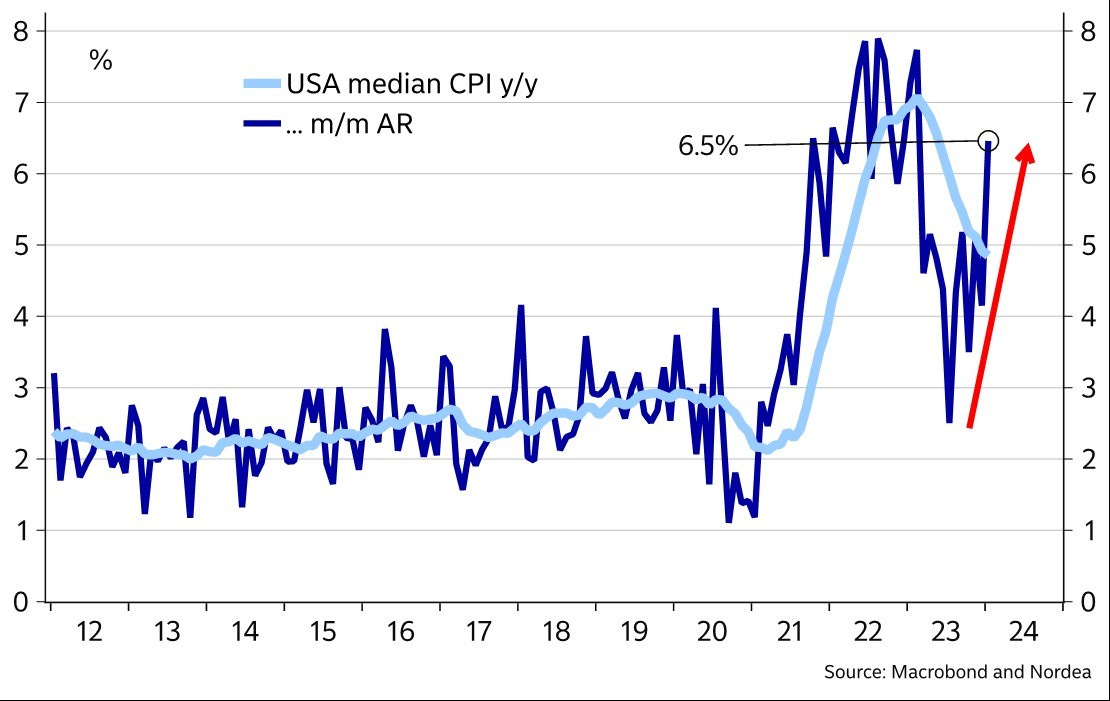

Median CPI, which excludes shelter, remains elevated.

Sticky CPI has never really moderated at all.

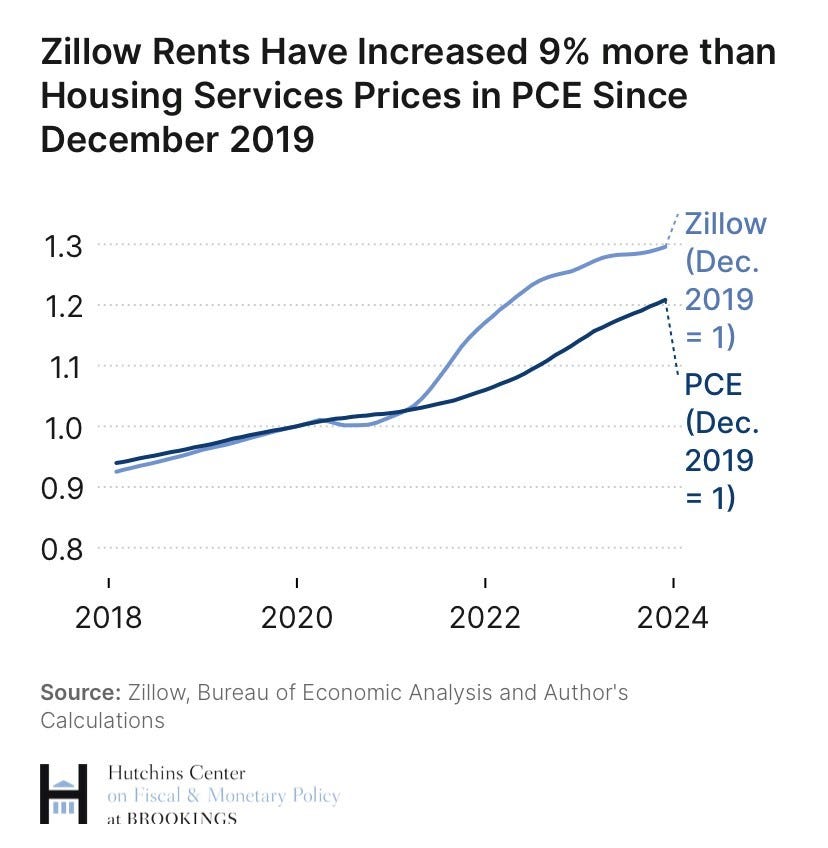

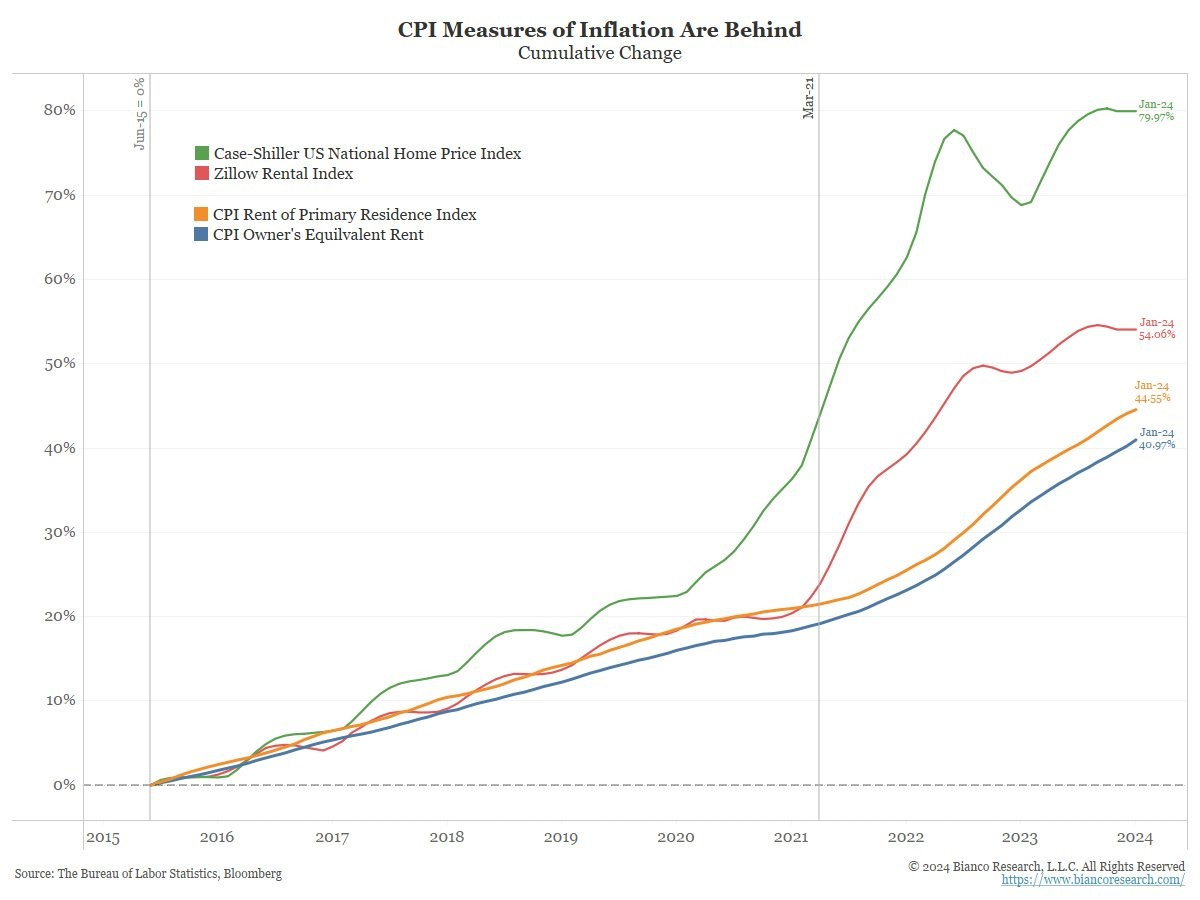

Everyone is banking on goods inflation to stay contained, and for shelter inflation to collapse. However, I have been hearing about the latter for 18 months, and with housing having bounced significantly over the last 12 months, with sticky demand from demographics, I struggle to see why everyone is so confident in it. It looks more likely to me that PCE Shelter significantly understates the real housing cost of what people are feeling in the economy.

Shelter is wonky, but I only see further catch up or strength, not much downside.

So, with a strong economy, I am less convinced inflation has been beaten to death, and that we all ride into the sunset with strong nominal growth and no stalling or pickup in inflation.

Additionally, it is undeniable that the massive easing in financial conditions supports growth. With household wealth at a record high 550% of GDP, sharp wealth gains support consumption. Lower rates support housing activity. With full employment, strong wages, strong household balance sheets, the economy moves on the margin. These marginal impulses lead to re-accelerations in activity from the status quo that transpired prior to these FCI easings.

The economy underwent two major re-accelerations last year that were preceded by 2-3 months from large FCI easings: Early 2023, with over 800k job gains in 2 months, and Q3, where we had nominal GDP over 8%.

The concern I have is both of those were smacked with tightenings from events not related to the Fed: SVB, and the term premium tantrum. What if we don’t get lucky this time around?

None of the above has me calling for rate hikes. What it does have me call for is no rate cuts. The mere mention of rate cuts in December led to extreme animal spirits.

The Fed’s framework is to think that because the Fed Funds rate is 5.375% and their estimate of neutral is 2.5%, unchanged from last cycle. On this basis, they want to cut rates because they think being 3% above the neutral is very restrictive and bad things will happen if they don’t. This makes no sense to me. If the economy is proving resilient to higher rates, maybe the neutral rate has changed. The Richmond Fed Lubik model has the real neutral rate at 2.17%, or 4.17% nominal, which is much higher than the Fed’s estimate that comes from the Williams model. It also did decline last cycle and has now returned to pre-2007 levels, thus it seems flexible and adaptable to the regime we are in.

My argument is this: due to the strong cyclical dynamics coupled with demographic changes, I believe the neutral rate has changed. I am not smart enough to come up with a precise level, but maybe the post GFC economy was the anomaly, not the norm. if I am wrong, let the economy show us that rates are restrictive and they have lots of room to cut and stave off a recession before it worsens. But do not cut based on hypothetical neutral rates when they very well might be wrong! Considering how poor the Fed’s own forecasts have been on everything from inflation, unemployment and growth, should we really base everything off a neutral rate forecast? These decisions are exactly how you get a second wave. A second wave would be disastrous. It is the scenario that leads to them hiking again, breaking the economy and a 10x worse recession than the one everyone is concerned about because “rates are too high”.

How would we get a second wave? If they misjudge the neutral rate, and cut, it will incentivize lending growth to pick up. We are currently growing above potential with only ~2% YoY lending growth. Thus, if lending picks up, at a time when money velocity has inflected higher, we are setting the conditions for higher inflation. Additionally, the stigma around rising prices is gone. Thus, given the experiences of the last 3 years, if companies see their input costs rise, they will surely feel more comfortable raising their selling prices than they were in 2021 when inflation was deemed “transitory”. The same goes for workers; the stigma around demanding larger wages is gone, so if inflation rebounds, expect workers to feel emboldened to ask for higher wages.

Due to both structural and cyclical reasons, I thus believe rate cuts at this stage would be a very risky proposition for the Federal Reserve. Given the strength of the economy, and the substantial policy room with the Fed Funds rate above 5%, I think waiting is the best policy as it gives them optionality to study the economy, understand its resilience to higher rates and the structural changes that are occurring. Additionally, by waiting for clear signs of economic weakness, they reduce the tail risk of an overheating economy and a second wave.

In conclusion, I do not think the bond bear market is dead yet.

The Great Demographic Reversal by Goodhart and Pradhan should be required reading for policymakers and the believers of a quick return to 2% inflation. I see your demographics argument echoes Goodhart and Pradhan. I would also add re-shoring (de-globalization) and decarbonization as inflationary factors.

Great article Danny!